Marine Reserve Benefits

No-take marine reserves are a relatively new thing in the world.

When the scientists of Auckland University's Leigh Laboratory set out to protect the waters around their lab in the 1970's, they didn't anticipate it would create a $18.6 million benefit to the local economy (Hunt, 2008).

The benefits of marine reserves to marine biodiversity are now well documented in New Zealand and international marine ecological literature. See our Library. Here we attempt to summarise those proven benefits.

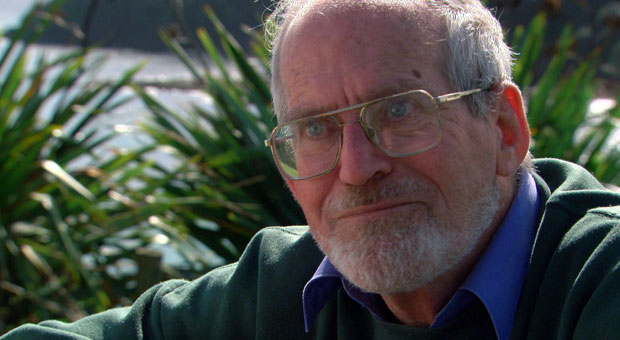

Dr Bill Ballantine, who passed away in 2015, was a marine scientist who lead the way in New Zealand and overseas in understanding the need for and value of networks of marine reserves. After 30 years of study into the benefits of marine reserves he reflected, "...our expectations are based largely on ignorance, we don't know much." The point here is that we have much to learn about the ocean: it is very big, very complex and largely unexplored. Marine Reserves are now areas, virtually the only areas, of the sea where we can learn about marine ecology in its natural state. Bill's 30 years of work in this field is largely preserved in an online resource. We strongly recommend anyone wanting to learn more about marine reserves, especially the benefits, to work through this resource summarised below:

Dr Bill Ballantine, who passed away in 2015, was a marine scientist who lead the way in New Zealand and overseas in understanding the need for and value of networks of marine reserves. After 30 years of study into the benefits of marine reserves he reflected, "...our expectations are based largely on ignorance, we don't know much." The point here is that we have much to learn about the ocean: it is very big, very complex and largely unexplored. Marine Reserves are now areas, virtually the only areas, of the sea where we can learn about marine ecology in its natural state. Bill's 30 years of work in this field is largely preserved in an online resource. We strongly recommend anyone wanting to learn more about marine reserves, especially the benefits, to work through this resource summarised below:

Here is the link to the Bill Ballantine's marine-reserve.org web site home page.

There is a page of his published papers, 22 in all that cover all aspects of the principles of marine reserves and discussion of the benefits: Marine Reserve Information page

There are three excellent Marine Reserve Powerpoint presentations created by Bill available on the site.

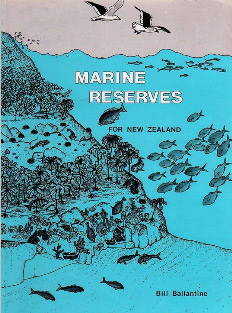

Bill produced a Marine Reserves Book, it remains the best campaign resource ever produced for people wanting to understand and work towards creating a marine reserve.

Precautionary Principle

Marine reserves provide the best insurance against the dynamic and often unpredictable changes in the sea. Our seas face new challenges every decade due to human activities. Global warming, ocean acidification, sedimentation, biosecurity threats and disease events are only a few. Scientists remain unable to agree on the impacts of combined pressures on the marine environment. In today's world a network of fully protected marine reserves is the strongest way to boost resilience in the marine environment. The precautionary principle is internationally practiced in environmental legislation and policy since it's inclusion in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development in 1992. "Where there are threats of serious or irreversable damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation". This principle is key to our Biodiversity Strategy 2000 and is an essential part of managing disease outbreaks, security threats and emergency response. We are yet to see the widespread use of the precautionary principle in ecosystems and resource management. Perhaps this is due to shifting baselines?

Marine reserves provide the best insurance against the dynamic and often unpredictable changes in the sea. Our seas face new challenges every decade due to human activities. Global warming, ocean acidification, sedimentation, biosecurity threats and disease events are only a few. Scientists remain unable to agree on the impacts of combined pressures on the marine environment. In today's world a network of fully protected marine reserves is the strongest way to boost resilience in the marine environment. The precautionary principle is internationally practiced in environmental legislation and policy since it's inclusion in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development in 1992. "Where there are threats of serious or irreversable damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation". This principle is key to our Biodiversity Strategy 2000 and is an essential part of managing disease outbreaks, security threats and emergency response. We are yet to see the widespread use of the precautionary principle in ecosystems and resource management. Perhaps this is due to shifting baselines?

Biodiversity – benefits to the fish in the sea

Putting people and their needs aside, the greatest benefit of a marine reserve is to 'life in the sea'. A significant proportion of our marine biodiversity is unique to NZ, where the marine environment takes up an area nearly 15 times larger than our land. It is estimated that 80% of NZ's species live in the sea. In comparison with other countries, New Zealand's part of the sea is particularly rich and diverse. From the subtropical Kermadec Islands in the north to the sub-Antarctic Islands in the south, hundreds of habitats are the home to over 15,000 known species. Yet, there is so much to be discovered. Scientists estimate our marine environment is home to over 65,000 species. Only 1% of our marine environment has been surveyed. NZers are the guardians of this biodiversity.

Bryozoans and jewel anemones at the Poor Knights Marine Reserve

Bryozoans and jewel anemones at the Poor Knights Marine Reserve

There are few ecosystems in the sea left in a natural state where all parts of the system are protected from the many ways people interfere with the sea. Of course we mean not only fish! Marine reserves benefit the smallest bryozoan as well as the largest ocean travellers. A thriving marine environment also influences life on land. At the Poor Knights large predators like kingfish drive smaller fish and krill shoals to the surface, which in turn are fed on by Buller's Shearwater who return to their burrows on the islands to feed their young. Here their burrows are shared by the ancient and rare tuatara. The seabirds that nest on the Poor Knights are doing a lot better than those on many other offshore islands, where seabird nesting colonies are declining.

Within a marine reserve, the ecosystem structure is left to its own balance with large kaimoana still part of the picture. The flow on effects of whole ecosystem protection are numerous and unpredictable from one marine reserve to the next. The famous example being Leigh Marine Reserve's kina (sea urchin) dominated rocky reef barrens. Within 8 years of full protection over 30% of the rocky reef had transformed from bare rocks to kelp forests, teeming with species that were not often seen before protection.

In marine reserves breeding retains more genetic diversity which adds resilience to populations. In the event of disease or change in the environment greater genetic diversity gives the best chance for populations to adapt and survive.

The combined biodiversity benefits of marine reserves could also be called ecological restoration. By doing nothing (as opposed to continued fishing etc) we can see a degraded marine environment return close to it's pre-human abundance, all within one lifetime. It is a lot trickier on land where just leaving a piece of land often results in pest invasion.

The creation of five North Island east coast no-take areas has resulted in at least 14 times more legal sized snapper found within these areas than within the neighbouring rocky reefs. And this is in despite of snapper being a transient species.If this could be translated to fishing effort needed to catch your limit in snapper, what normally may take 3 hours (which would be pretty good going in most areas), the abundance of the marine reserve would have you fill your bag in less than 13 minutes!

Scientific benchmark

Scientists initiated the first marine reserves in NZ to provide a control against which change can be measured. All of NZ's mainland marine reserves could be considered small (eg less than 50,000 ha) as they protect only a small part of their transient species' ranges. Yet, from these we have learnt so much. There are hundreds of studies comparing ecosystem structure, food webs, ecosystem resilience, abundance and behaviour inside and outside the reserves, giving us insight into the amount of change caused by widespread human interference. This provision of a benchmark enables us to 'ground truth' any modelling on the effects of our marine and fisheries management, essential to ensuring sustainable fisheries.

Maintaining a baseline

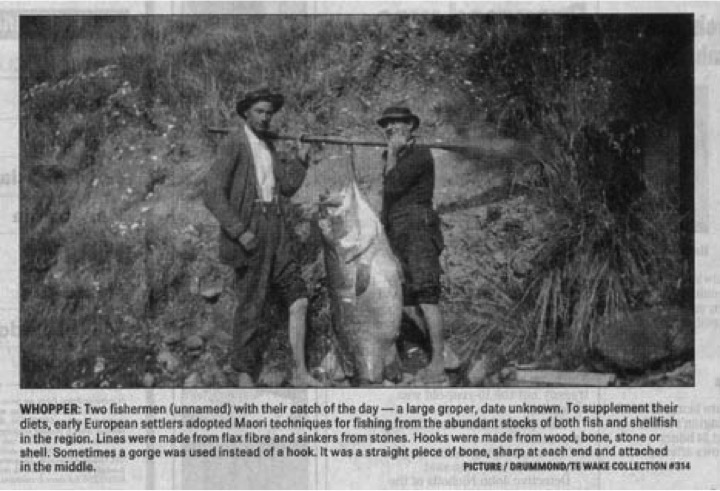

In social consciousness, our baselines of what is normal and acceptable changes from generation to generation. In the case of fishing, our baselines have been sliding towards smaller and smaller fish being the norm. Some call this the slow motion disaster. Marine reserves give us a face to face reminder of what should be considered 'normal' in biodiversity terms.

Education & inspiration

Marine reserves provide inspiration for integrated learning in nearly all areas of the NZ curriculum. They provide a wet library for experiential education. Within a marine reserve, face to face connections can be made with the physical world and biological sciences in a natural setting, unlike a zoo. By seeing a thriving and abundant marine environment students are inspired to learn, and to take up the challenge to act as a guardian of the sea. This underpins the Experiencing Marine Reserves Programme, founded in Northland NZ by the Mountains to Sea Conservation Trust. After experiencing their local marine environment, and comparing it with a fully protected marine reserve, the inspired students on this programme have carried out hundreds of positive actions for the marine environment. We believe that every school in NZ should have access to a marine reserve, a place to learn about the natural state of our seas.

Economic benefits

Take a quick trip to Goat Island (Leigh) Marine Reserve on a hot summer day and you can immediately see a thriving local industry based around the marine reserve. 250,000 visitors per year provide work for snorkel and dive businesses, ice cream vendors, the glass bottom boat and camping grounds. A 2008 study (Hunt, 2008) showed 54% of day visitors said they wouldn't visit if it wasn't for the marine reserve and that these visitors contribute $18.6 million per year by direct spending and flow on effects in the local economy. A financial benefit to marine reserves has been demonstrated the world over (see this National Geographic article).

Take a quick trip to Goat Island (Leigh) Marine Reserve on a hot summer day and you can immediately see a thriving local industry based around the marine reserve. 250,000 visitors per year provide work for snorkel and dive businesses, ice cream vendors, the glass bottom boat and camping grounds. A 2008 study (Hunt, 2008) showed 54% of day visitors said they wouldn't visit if it wasn't for the marine reserve and that these visitors contribute $18.6 million per year by direct spending and flow on effects in the local economy. A financial benefit to marine reserves has been demonstrated the world over (see this National Geographic article).

In NZ marine reserves have also attracted the promotion of Air NZ. This corporate partnership with the Department of Conservation focuses on supporting marine reserves monitoring and research, along with direct promotion of the marine reserves to international visitors. It is expected that any clear water, accessible marine reserves will cause some increase in tourism with positive economic impacts, but could there also be positive economic impact to fishing industries?

Fisheries benefits

Not only theory and modelling have shown that well designed networks ensuring representative protection, replication and adequate sized no-take marine reserves benefit commercial and recreational fishers. This is proven via spillover of harvestable stock as well as recruitment to fishing stocks being higher within marine reserves. Published cases of this benefit include a world class recreational fishery alongside the USA's oldest no-take area in Florida, and cray pots lining the boundaries of NZ's first marine reserve at Leigh. In one study a roman fisheries catch per unit effort (CPUE) doubled 10 years after a 40 km2 area was protected in South Africa, despite fishers no longer having access to a large part of the previously fished coastline.

Another common theme in no-take marine reserves the world over is changes in behaviour, especially of exploited species. These fish are less wary of people and larger fish 'show the way' to younger fish. Through spillover these behaviours are seen outside marine reserve boundaries. An Auckland University scientist (Willis et al., 2003) published studies on marine reserve benefits to snapper suggesting that "...protection of fish populations within reserves might slow reductions in genetic diversity caused by size-selective mortality brought about by exploitation." Outside a marine reserve snapper are shy. These behaviours may be handed down in their genes which over time would cause change in the fishing methods needed to catch them.

The above benefits to fishing are in addition to the insurance scheme marine reserves provide. In the case of overexploitation, well stocked marine reserves can help rejuvenate fisheries, preventing local extinctions and contributing to long term sustainable management.

Social benefits – the sea is all of ours

A group of EMR snorkelers investigating their marine reserve It doesn't stop at education inspiring the next generation of biologists. After a marine reserve is gazetted it becomes the property of all NZers. Just like our national parks on land, a network of marine reserves would showcase the diverse marine environment at it's best. A place for recreation and art, they are a source of local and national pride.

A group of EMR snorkelers investigating their marine reserve It doesn't stop at education inspiring the next generation of biologists. After a marine reserve is gazetted it becomes the property of all NZers. Just like our national parks on land, a network of marine reserves would showcase the diverse marine environment at it's best. A place for recreation and art, they are a source of local and national pride.

Gazetting also attracts extra management resources through the Department of Conservation. In many reserves these management budgets are governed through local committees made up of representatives from the community, tāngata whenua and fishing interests. In this way marine reserves encourage working together and the sharing of ideas and values. For example, an unexpected outcome of the Te Tapuwae o Rongokako Marine Reserve near Gisborne has been a collaborative catchment restoration effort, in order to reduce sedimentation and other land based effects on the marine reserve. Read more in our Te Tapuwae o Rongokako Marine Reserve Case Study.

Many marine reserves share our cultural history, telling stories in their names (Read page 10 on the naming of Te Tapuwae o Rongokako) and protecting sites of historical importance like the shipwrecks of Taputeranga in Wellington.

Protection of Cultural Values

The current Marine Reserve Act 1971 does not include sections specifically addressing cultural and tāngata whenua values other than provisions for customary take in marine reserves. However the Marine Reserve Act is subject to Treaty provisions and priniclples in the Conservation Act. In recent efforts to amend the Marine Reserve Act there are more up to date Treaty references signalling the Government's future intent. The Director-General and Ministers of Conservation and Primary Industries are bound to consider the crown's partnership with tangata whenua and the Treaty of Waitangi in any and all of their roles through separate legislation. This can work out in favour of protection and recognition of cultural values, such as in the management of Te Whanganui a Hei Marine Reserve – Cathedral Cove. The waahi tapū of importance to local hapū Ngāti Hei is recognised and protected due to submissions made during the application process. Likewise in the Long Island – Kokomohua Marine Reserve in the Marlborough Sounds the marine reserve order includes proteciton of local tāngata whenua rights to take serpentine and nephrite from within the reserve.

Ahipara Takutaimoana Committee erect a Pou to open the Rahui at Tauroa Pt, Ahipara

Ahipara Takutaimoana Committee erect a Pou to open the Rahui at Tauroa Pt, Ahipara

Some iwi and hapū members believe marine reserves clash with the ability to practice manaakitanga (hospitality) and tino rangatiratanga (self determination). Yet, marine reserves are already used by some iwi and hapū in their local resource management. In Rakiura's Ulva Island Marine Reserve, spillover takes place into the surrounding Whaka ā te Wera Mātaitai Reserve. Similarly the Tan garoa Suite of Ngāti Kanohi brings the Hakihea Mātaitai, Te Tapuwae o Rongokako Marine Reserve and a planned Taiapure together enacting active co-management of their entire rohe moana as outlined in this DOC report.

A Northland hapu group at Tauroa Pt, Ahipara Takutaimoana Committee has relied solely on their traditional authority and tikanga to establish a rahui for the protection and restoration of local shallow reefs and paua and crayfish.

What is clear is that we need to find locally appropriate ways to partner with Maori to care for the marine environment. Marine Reserves are one of the tools that can be used.

There are more resources on benefits in our Library Archive Social Science and Community Consultation.

There are many discussions on benefits of marine reserves appearing in the Case Studies and Marine Reserve Applications and Proposals Library Archives.

Also see our pages on Fisheries Act and Customary Tools and Supporting Customary Management

Marine Protection in New Zealand is in a period of change. For a long time there has been a desire to change the legislation. The Government in 2016 released a

Marine Protection in New Zealand is in a period of change. For a long time there has been a desire to change the legislation. The Government in 2016 released a  The government wants coordination of the MPA planning process in regional community based Marine Protection Planning Forums (MPPF) (MPA forum process) made up of stakeholder representatives that will be supported by DOC and MPI staff, and tasked to work towards consensus on a recommendation report to the Ministers within 18 months of their formation. The key steps to follow include:

The government wants coordination of the MPA planning process in regional community based Marine Protection Planning Forums (MPPF) (MPA forum process) made up of stakeholder representatives that will be supported by DOC and MPI staff, and tasked to work towards consensus on a recommendation report to the Ministers within 18 months of their formation. The key steps to follow include: