A happy and proud dad at an EMR eventThe ultimate aim of a marine reserve project is the establishment of a marine reserve resulting from a process where the community has increased its awareness of marine conservation and grown to support the reserve proposal. Community support for marine reserves is fundamental to the success of any one reserve. Marine reserves depend on a very high level of compliance and this can only be achieved with the support and full involvement of the local people. The legislation which creates marine reserves (currently the Marine Reserves Act 1971) requires that all members of the local community who are affected by a marine reserve are informed of the proposal and consulted.

A happy and proud dad at an EMR eventThe ultimate aim of a marine reserve project is the establishment of a marine reserve resulting from a process where the community has increased its awareness of marine conservation and grown to support the reserve proposal. Community support for marine reserves is fundamental to the success of any one reserve. Marine reserves depend on a very high level of compliance and this can only be achieved with the support and full involvement of the local people. The legislation which creates marine reserves (currently the Marine Reserves Act 1971) requires that all members of the local community who are affected by a marine reserve are informed of the proposal and consulted.

This page covers some key points to cover prior to embarking on this project. More specific detail looking at working with specific groups within your community and introducing background resources is found on our Working With Your Community page.

Once consultation is underway, you will find that many rewarding moments come from the process of engaging your community in discussing the establishment of marine reserves. Often people are put off by the fear of facing extremely vocal opposition, but this experience is the exception rather than the rule. You can train yourself on how to deal with the vocal opposition. Fortunately reason, common sense and overall public support are clearly on your side. Here we attempt to arm you with the learnings of past campaigns and best practice models. The focus of this information on consultation is structured around creating a marine reserve proposal and then ultimately a marine reserve application. However most, if not all of this process would be useful and productive if your proposal is heading for a marine protection forum process. Good engagement with community and effective consultation will always be part of and needed in any marine protection forum we use in the future.The DoC Handbook for Applicants provides general consultation guidelines at pages 8-12.

Following some general advice, we then move on to some more specific advice focusing on the groups that are likely to become most important in your consultation efforts.

This is DoC's minimum checklist of groups to engage with in consultation or involve as participants:

➢ Local iwi and tangata whenua

➢ Commercial fishers (including marine farming)

➢ Recreational fishers

➢ Community groups

➢ Tourist operators

➢ Landowners

➢ Dive clubs

➢ Boat clubs

➢ Local authorities

➢ Ministry of Primary Industries

➢ Research organizations such as universities

➢ Environment groups

➢ Department of Conservation

➢ Relevant Conservation Board

➢ Schools

For more detail and notes on engaging with specific groups in your community go to our next page Working with Your Community.

Prepare yourself

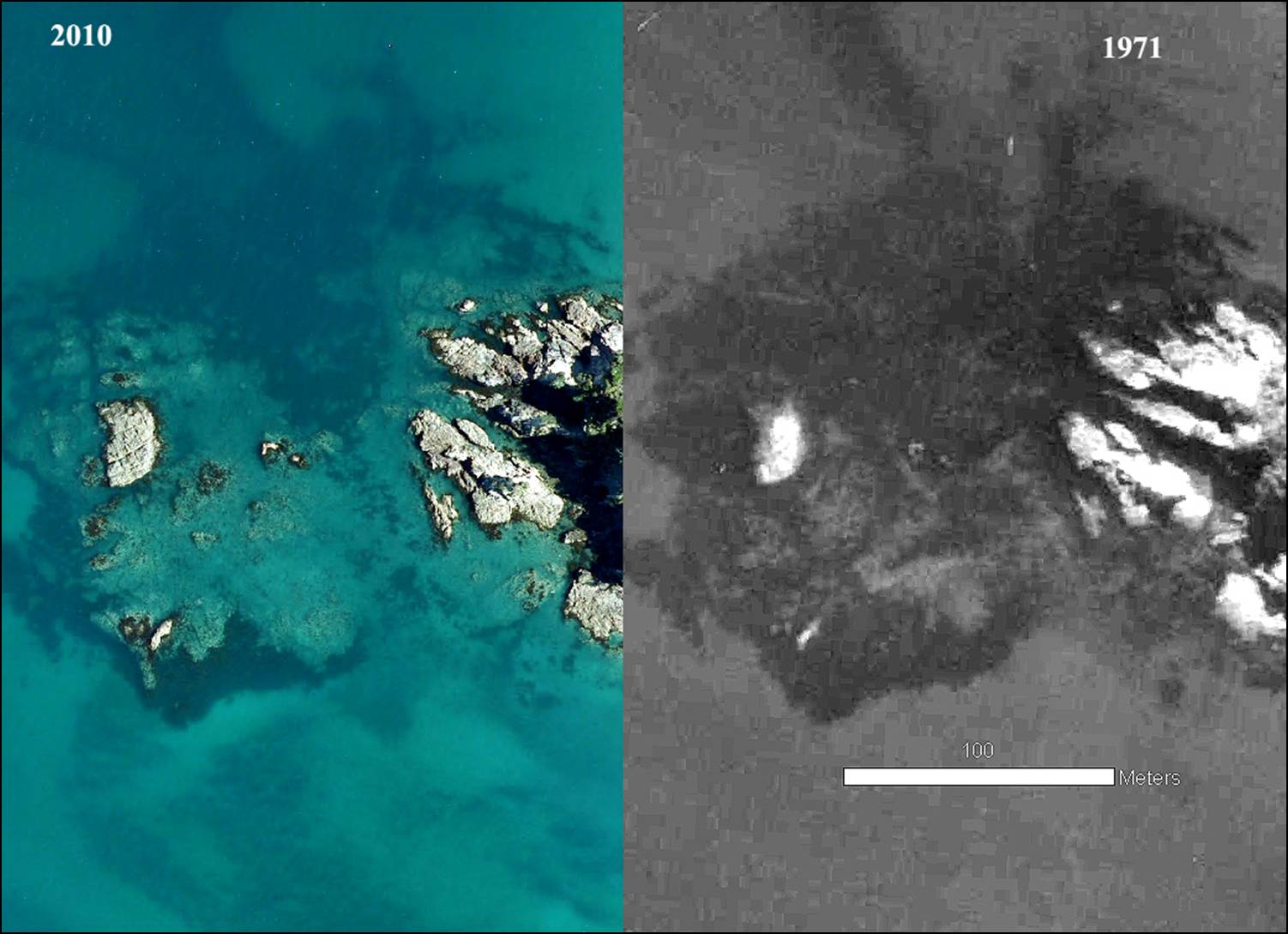

Dramatic illustrations of kelp forest decline like this in BOI tell the storyMarine Reserves are a proven biodiversity conservation tool, and they have widespread public support.

Dramatic illustrations of kelp forest decline like this in BOI tell the storyMarine Reserves are a proven biodiversity conservation tool, and they have widespread public support.

Study the information in this Kit thoroughly and prepare a dozen short topics to talk about that support the establishment of marine reserves or reserve networks. Making your own slideshow talk or Powerpoint presentation is a good way to organize your thoughts.

Any and every marine reserve proposal will be faced with vocal opposition, strong vested interests and a minefield of red herrings. The positive path through this is: vocal opposition creates an opportunity to respond with intelligent questions about what's actually important, and red herrings are a chance to talk about what is really happening in the ocean with regard to conservation and marine reserves.

Denials, Distractions and Dead Ends

The following excerpt is taken from the late Dr Bill Ballantine's course ENVSC1726, Principles and dynamics of marine reserves. It lists common objections to reserve establishment. Forewarned is forearmed...

The other pages in this objection-handling folder are from the late Dr Ballantine's website, all are all short, to the point and immensely useful in a campaign situation:

Below is a list of objections to marine reserves and other arguments that prevent effective progress, but which are largely irrelevant, illogical or untrue. In practice, opponents of marine reserves generally use a range of these and move quickly from one to another if a good counter argument is produced on any one. Since the available list is long (and each one has many variants) this tactic can maintain the argument indefinitely.

It is noticeable, however, that ordinary citizens are often impressed by arguments in Class I (until they hear careful counterpoints). Politicians, administrators and others who pride themselves on being pragmatic are particularly affected by Class II. Scientists and intellectuals are especially prone to belief in Class III. Local objectors to particular proposals often use arguments in Class IV.

I Denials of the marine reserve concept: objections on 'principle'

1. People are part of nature, everything they do is 'natural'.

2. What's the problem? "If it ain't broke, don't fix it."

3. Universal fishing is a right, unless there is a clearly defined problem.

4. Indigenous peoples' fishing (or other cultural uses) cannot be disturbed.

5. Displaced fishing and/or fish mobility will ensure there are no real benefits.

6. Protection must be absolute so people must be excluded from reserves.

7. 'Reserves' should be opened to fishing at intervals.

II Distractions based on alternatives that are more 'practical'

8. Improved detailed management on existing lines is the answer.

9. General planning in the sea (e.g. multi use zones) is the answer.

10. Aquaculture is the answer.

11. Active restoration of stocks (e.g. breeding and release) is the answer.

12. Fish aggregation devices (FADS) and/or artificial reefs are the answer.

13. Other problems are more important and must have precedence.

III Denial of system principles: insistence on precise justification

14. 'The purpose' of each reserve must be defined by sector and/or stock.

15. Reserves must be located in the 'right places'.

16. Surveys and data are needed to locate the 'right places'.

17. Monitoring is necessary to 'show success'.

18. Success is when there is 'more and better' inside than out.

19. People overcrowding in reserves destroy their purpose

NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard): insistence on special/local justification.

20. Each proposed area has important current uses.

2 1. Each proposed area is not sufficiently special to justify the restrictions.

There is a further exploration of objections to be found within Bill's marine reserve course. It goes into the area of how to think about and respond to objections. Each of topics are short, to the point and immensely useful in a campaign situation. Download Objections Explored.

It is really important in these early stages of engaging with community that you keep your cool and are respectful of peoples culture, ideas and even opposing opinions. People typically take considerable time to understand what marine reserves are all about and what they actually do. And even more time to appreciate the benefits. But rest assured that in time people do appreciate the benefits, especially once the have a marine reserve in their area. Having said this it is extremely useful to learn as much as possible about these objections and how to respond to them in a respectful and positive manner. Practice it will help. Practice how you will agree to disagree. Practice asking questions to gain better understanding rather than reacting and opposing - this one strategy is very useful in handling angry objections.

Key Points and Learning from the Past

The early stages of a marine reserve campaign are the most productive ones

- Build a base of marine biodiversity awareness

Many commentators on consultation and environmental campaigns stress the importance of the need to foster education, involvement and experience. This basic rule applies to the marine world probably more than any other environment. This is because we face the challenge that most people do not experience the marine environment to any great extent. Even frequent users of the marine environment only experience tiny fractions of what exists. It is the last great wilderness, which unfortunately is now under threat.

1,000 Northland students celebrate the opening of Whangarei Harbor Marine ReserveAs an example based in Northland The Mountains To Sea Conservation Trust has built its education, community engagement and experience to the highly successful program Experiencing Marine Reserves. This program is working and has now introduced tens of thousands of young and old New Zealanders to a hands on experience with a local marine reserve. We see unlimited potential for further development. We suggest that you evaluate our resources, our strategies, and adapt the concept to your campaign and community. Seek out partners to help you with this process.

1,000 Northland students celebrate the opening of Whangarei Harbor Marine ReserveAs an example based in Northland The Mountains To Sea Conservation Trust has built its education, community engagement and experience to the highly successful program Experiencing Marine Reserves. This program is working and has now introduced tens of thousands of young and old New Zealanders to a hands on experience with a local marine reserve. We see unlimited potential for further development. We suggest that you evaluate our resources, our strategies, and adapt the concept to your campaign and community. Seek out partners to help you with this process.

Beyond the basic level of awareness and engagement, the next fundamental task is to involve key stakeholders in your project at absolutely the earliest opportunity. There is nothing wrong with going to stakeholders at the very beginning of your project and asking for their support. It is good practice to ask stakeholders how they think consultation should be done and who they suggest would be appropriate contact people for you. The common and tragic mistake, easy to make, is to focus on always gathering more information before you go and talk to key stakeholders or to delay the most difficult contacts or groups perceived to be in opposition to the end of the process. This will always prove to be counterproductive and should be avoided. Go to the hard places first.

Seek Iwi/Hapu support and involvement as a first step

There are virtually no coastal areas of New Zealand which are not under traditional authority of a tribal group. It make sense in the context of the Treaty obligations reflected in the Marine Reserve Act to pay local tangata whenua group(s) the respect of going to them first and explaining to them your intentions.

In a traditional sense this is an action that is very important and will result in your actions and intentions being respected and received, regardless of whether your ideas or proposal is initially agreed to. As a general rule you should make sure that either you or someone helping your group has a good knowledge of local protocol to make this first visit and engagement a positive one. Again, this is a basic demonstration of respect on your part.

For more detail and specific notes on working with iwi/hapu in your community go to our next page, Working with Your Community.

Some useful messages from marine reserve campaigners

This is an excerpt from a Bay of Plenty Polytechnic Diploma of Marine Studies project by Michael Stewart, October 2002, entitled The Processes Involved in a Marine Reserve Proposal. This is his advice for people entering the consultation process (as he did) for the first time:

"In the future I would use my time to concentrate on the consultation process earlier, and I would not attempt to cover such a broad range under one topic in such a small space of time. Performing the consultations affected the outcome of the draft proposal. A detailed timeline is required in order to be able to organise yourself efficiently, however, when consulting with the likes of local Iwi, residents, and fishers, along with government agencies such as the Department of Conservation, Ministry of Fisheries, the consultation becomes a process that you cannot map out in front of you. You start from a certain point and go from there, meeting with different people along the way, and being referred to other people. Another problem I had with the consultation process was trying to contact people at convenient times. Generally it is very difficult to get hold of people over the phone. This is where a visit becomes necessary."

This article is taken from the Mimiwhangata Communication Plan by Vince Kerr, May 2002.

"The Language of a Marine Reserve Campaign"

Don't forget to mention that people love marine reserves, a busy day at Leigh Marine ReserveA perfect community relations situation - in which community and iwi interests are approached with a truly open agenda - has yet to be encountered in New Zealand marine reserve work. This however can change, once there is more emphasis on a strategic network design process that incorporates true community participation. Past experience has shown that early education and awareness building efforts alongside the earliest possible engagement and consultation with affected parties are extremely valuable to the eventual success of a campaign.

Don't forget to mention that people love marine reserves, a busy day at Leigh Marine ReserveA perfect community relations situation - in which community and iwi interests are approached with a truly open agenda - has yet to be encountered in New Zealand marine reserve work. This however can change, once there is more emphasis on a strategic network design process that incorporates true community participation. Past experience has shown that early education and awareness building efforts alongside the earliest possible engagement and consultation with affected parties are extremely valuable to the eventual success of a campaign.

In any campaign it is vital to use language that consistently reflects our intent (including legal distinctions) and our actions. This is a first principle of community relations. So here is a marine reserve campaign language lesson:

• We are engaged in the investigation of marine conservation options for [your area]. We are interested in investigating a marine reserve option. We are currently in consultation with the community and iwi to seek their views and guidance. [Do not use the term proposal; one does not exist yet. Note the use of the words conservation and interested.]

• Provided technical work is complete and initial consultation reveals support for the marine reserve concept, a draft proposal is launched publicly. From this point we are working with a proposal. This marks the beginning of an informal, (non-statutory), submission period and further consultation rounds.

• When we are satisfied the proposal is worth proceeding with through the statutory process, a formal application is prepared to meet the requirements of the Marine Reserves Act 1971. This application is then publicly notified starting a two month public submission period. From the notification date the process becomes a statutory one, subject to full legal scrutiny. All of the process is about the public and stakeholders having full access to information and having their say! This has to be constantly emphasized and repeated! Only when all this process is completed does the process of decision making begin at Ministerial level.

Be crystal clear on the use of the three words: Investigation, Proposal, Application.

Role play using these keywords to describe the process, giving brief updates on your campaign to: the press, local iwi, fishing clubs, etc.

The consultation process is absolutely dependent upon the way a local community PERCEIVES the campaign – and the campaigners."

For more detail on working with specific groups within your community and background resources go now to our Working With Your Community page.